About Time You Met: Patrick HughesBy Suzi Malin

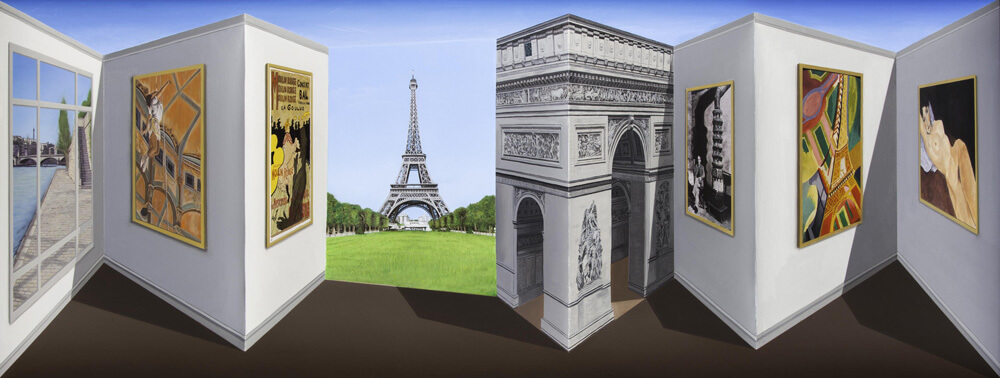

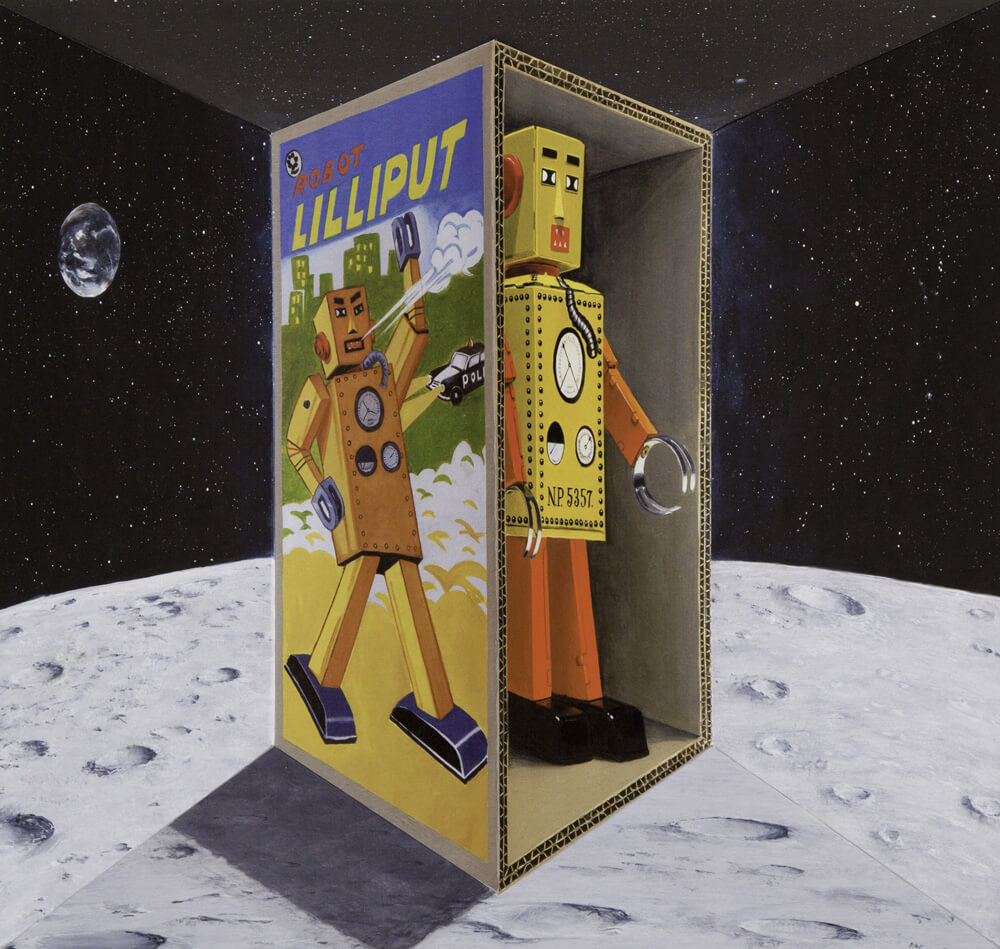

Patrick Hughes has a magic playbox of a mind. His genius lies in the fact that he reverses the complicated rules of perspective so his paintings move before your very eyes. But the greater part of his gift is that he makes these rules accessible to the man in the street. The viewer is held in fascination and enjoys Patrick’s reverse perspective like a child mesmerised before Christmas lights.

Patrick Hughes is playing visual games. He loves humour but beneath the man is multi-layered, multi-faceted and both light-hearted and serious at the same time.

Patrick shows me his studio. Ten workers sit at easels doing trompe l’oeil painting; each easel holds a separate painting. There are many commissions on the go, four for a Mexican collection showing opening doors with landscape beyond. One moment the doors appear open but as you move they gradually close.

I ask Patrick to open up about his life, which he does most endearingly.

Me: What do you want out of life?

Patrick: I want to live. I’m conscious that I’m dying. I think about it every day. I want to live on after I’m dead. I want people to like my work and continue to do so after I’m gone. Whilst Magritte was alive, you had the example of his boring real-life behaviour but after his death, you had the best of him – his imagination.

What I want out of life is to enjoy it to the full and I do, I enjoy mine a lot. I suppose I had my mother as an example of how not to live my life she was anti-social, mean, depressed, suspicious, ignorant, humourless, lazy. I never wanted to be like her. I did not go to her funeral.

Me: What do you love?

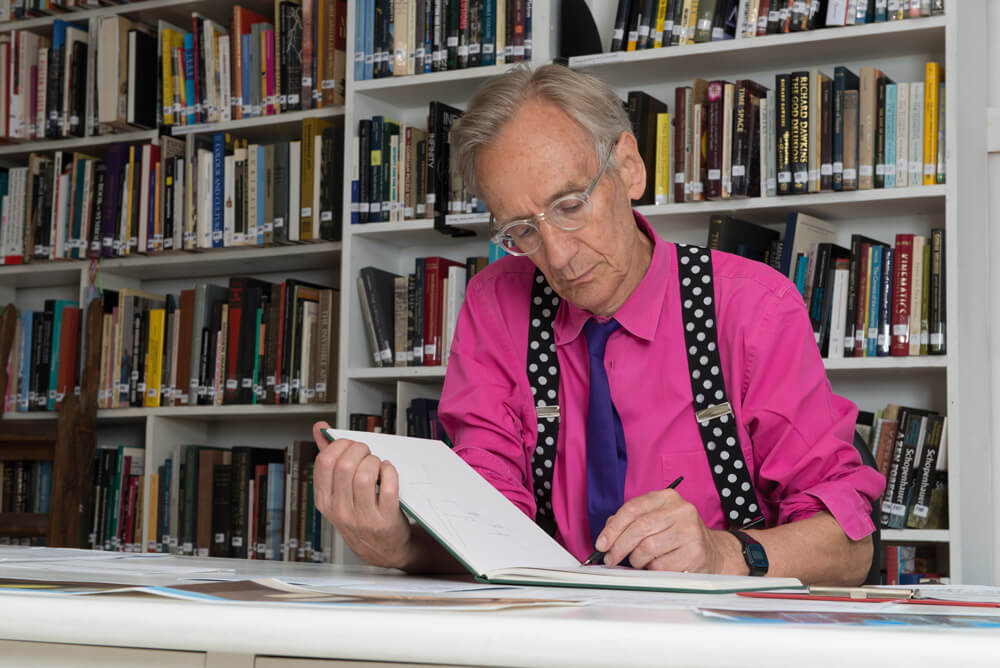

Patrick: I love reading a lot.

(He sits behind a massive indexed library of books.)

I’m reading the 3rd volume of the biography of Kafka at the moment. I also enjoy the theatre and go once a week, mostly to see comedy. When I was a boy I wanted to be a comedian.

Me: I guess, in a way you are a visual comedian.

Patrick: Yes, I am.

Me: What was your highest high creatively speaking?

Patrick: I think my creative highs were when I was young and first painting in my 20s and 30s – many of the ideas came to me then. I have been living off those for the rest of my creative life. You can live off your back catalogue like Dylan Thomas.

Me: Can you identify the happiest moment in your life?

Patrick: I’m always happy. The only time I went on Valium was for ten days when I was in love, split from my girlfriend and wasn’t sure if she’d have me back. It was prescribed by Dr. Slack, who gave speed for depression and Valium for anxiety. All he had to do, he said, was distinguish between them or Valium would make depression worse and speed would make you more anxious.

At that moment Patrick’s wife of 50 years Diane briefly enters wearing a tinsel Christmas halo. Of course she does. It is 11 am and this halo remains fixed for the rest of the day. This is the home of mild eccentricity and Bohemia and what else would she wear at this festive time? I ask her why she is so happy and she replies that her mother told her she was the best girl in the world every day of her life.

She disappears and Patrick continues to compare his experiences of childhood:

Patrick: I prefer an uphill struggle, adversity. My career hasn’t always gone smoothly. I left home at 17, I was an underage drinker at the Colony club. When I was 47, I was living in a squat in Islington with my son James. I didn’t have a phone or any means of sustenance. Thankfully the house was free, and I had a £100 car and a £2000 suit.

Me: Usually it is the house which is the most expensive and then the car but thirty years ago £2000 on a suit was an absolute fortune.

Patrick: I have always done things in reverse.

Me: Like your art? If you could live your life in reverse, like your reverspectives, what would you change?

Patrick: I haven’t always done well. I’m an eccentric, an outsider. I have been passed over by the cathedral of art, the Tate modern. I think it’s because I am so popular but also because I didn’t go through formal art training which would have given me an official standing. I am a republican. No Royal Academy or Royal College for me.

Me: Can you change that perception of you now?

Patrick: People go to the Tate because it’s religious, it’s full of relics and saints – drunken bums like Jackson Pollock, and the priests in black suits explain the arcane works to us. My work does not need an explanation to get it.

Me: What makes you happy?

Patrick: Exercise makes me happy. I have been exercising all my life. For thirty years I used to swim every day but for twenty years I’ve run six miles every other day. It not only makes me happy but also gives me energy.

Reading makes me happy and gives such great pleasure, as I am self-educated. When people have been to university they think they have been educated and can relax. They cannot because education never stops. I am the most learned person I know in the world of art in writing and learning because I have never stopped.

Me: Tell me about your earlier work, which featured images of the rainbow?

(I am referring to the series of work that sold 1 million postcards and 10 thousand rainbow prints)

Patrick: I have done most things with the rainbow, a most clichéd and powerful symbol – wrapped it, made it black and white, in fact did everything I could think of to bring it back to life. You see, the rainbow is a natural phenomenon but people have turned it into sentimental claptrap. Me doing images of the rainbow was a hot potato – like a seagull getting hold of a cold chip.

Me: About your work today? Your reverse perspective paintings of Venice canals?

Patrick: Venice is a also a cliché … just like rainbows. The good thing about Venice is that in terms of what I am doing, the buildings are all the same height. I don’t think Venice is wonderful. Venice is ironic, oppressive and claustrophobic. My pictures of Venice in reverspective are about reverspective not Venice.

I don’t like Venice.

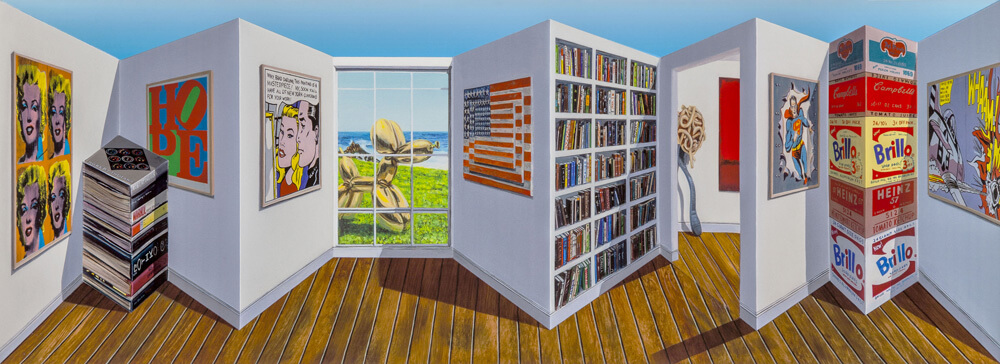

Me: You also paint libraries.

Patrick: Libraries aren’t interesting. Books are things, but reading is an eye opening experience.

Me: What advice would you give to an artist working today?

Patrick: You have to see everything that everyone has done in the last 120 years. You have to know what’s gone before in order not to do it again. But most importantly, you have to persist with your own madness. You have to be a fanatic, to know the complete oeuvre of those by whom you are influenced, go through it and come out the other side.

Me: And what is your favourite work?

Patrick: I think, at this moment my work depicting the stairs in 3D.

He shows me a white, newly primed structure of stairs in reverse perspective, the stair which disappears being closest to the viewer. It is awaiting painting though it looks very exciting unpainted in its white state. There are racks and racks of unpainted structures in their virgin state, primed and ready to go upstairs to the assistants.

Me: Why do you have a visual or emotional attachment to this image in particular?

Patrick: Come, I’ll show you!

He takes me to a tiny under stairs cupboard where, when one looks upwards, the stairs are seen in reverse.

Patrick: My mother and I used to hide under the stairs together in the war. Hiding together from German bombs.

Yes I understand. I understand that despite dreadful memories of his mother who was a beacon in his life showing him how not to live it, those intimate moments of fear shared together were the inspiration of the core of his fascinating artworks and his life’s visual journey.

All images are (c) PatrickHughes, Courtesy of Flowers Gallery London and New York. Portrait photographs by Lawrence Lawry. The exhibition Patrick Hughes: Patrickspective, organised in collaboration with Flowers Gallery, is on display until 30 January, 2017 at 45 Park Lane, Dorchester Collection, just near Oxford Street so if you are shopping or going to the sales, whatever you do … don’t miss it! www.flowersgallery.com.